One book that I frequently recommend is “The Merchants of Doubt” (see here). It was even made into a documentary film. The authors document the decades-long campaign of misinformation orchestrated largely by a small group of “reputable” scientists with the goal of discrediting any legitimate arguments against DDT and other hazardous pollutants, ozone-destroying CFC propellants and refrigerants, acid rain caused by coal burning, tobacco and its links to lung cancer, and most recently man-made climate change.

These scientists employed well-refined tactics to delay any meaningful reform in these areas. Essentially, their strategy was to create doubt about these dangers. As long as they could manufacture even the thinnest illusion of doubt, they could delay any efforts to restrict those industries. They succeeded for a long time – and still succeed with climate change – but only with the complicity of mainstream media organizations that publish their made-up arguments over and over again because they create bankable controversy and bolster the impression that their media coverage is fair-mined and impartial.

The New York Times has consistently been, unwittingly or not, one of the most influential misinformation machines for these merchants of doubt. And they are still helping them out. The other day they published an opinion called “God Is a Question, Not an Answer” (see here). In it, author William Irwin, a Professor of Philosophy at King’s College, puts forth ridiculous arguments in an attempt to discredit atheism. Or, more specifically, to create doubts about the fundamental intellectual validity of atheism.

Irwin claims that any reasonable, intellectually honest atheist must admit some possibility that god might actually exist. This is the exact same manipulation that pro-tobacco advocates put forth for years – surely any scientist with integrity must admit that he has some doubt that tobacco causes lung cancer. Similarly, Irwin attempts to shame us at least into a position of agnosticism that legitimizes religious belief. He says:

“Any honest atheist must admit that he has his doubts, that occasionally he thinks he might be wrong, that there could be a God after all …”

“People who claim certainty about God worry me, both those who believe and those who don’t believe. They do not really listen to the other side of conversations, and they are too ready to impose their views on others. It is impossible to be certain about God.”

These are false and totally ridiculous assertions. The only people that actually worry me are those that express any doubt whatsoever. As to the first claim, it is simply as silly as if one said:

“Any honest atheist must admit that he has his doubts, that occasionally he thinks he might be wrong, that there could be an Easter Bunny after all …”

This is a totally fair substitution since God has not one iota more factual credibility than the Easter Bunny. And again – just as with DDT, and tobacco, and CFC’s – the New York Times is complicit in helping to propagate and maintain this illusion of legitimate doubt by publishing this article.

I don’t condemn the New York Times for printing a viewpoint that doesn’t agree with me; I don’t condemn them for publishing a wide range of ideas; and it isn’t my goal to muzzle free-speech; but it is fair to criticize the New York Times for publishing harmful factual nonsense – just as they did in all those other areas so well documented in the Merchants of Doubt. And facts aside, this particular article is not even theoretically sound as an intellectual debate or legitimately valid discussion.

Make no mistake, belief in god is harmful factual nonsense. And this campaign to create intellectual doubt has been working. Even the vast majority of my atheist friends have been at least partially influenced by this argument and shamed by articles like this one, published by respected organizations like the New York Times, into a false position of agnostic intellectual “honesty.” But in my opinion, the only intellectually honest and courageous position is that there simply can be, is no god.

I would have come away dispirited and disappointed by this article, but happily the New York Times readers are far more intelligent and less gullible than New York Times contributors and reviewers. When I scanned the more than 750 comments, I found that essentially all of them see right through this nonsense for exactly what it is. The vast majority were clear-eyed and astute in calling bullshit on this transparent manipulation.

That makes me VERY encouraged. When merchants of doubt like William Irwin have to resort to manufacturing doubt, it is an admission that they know they cannot win on the merits of their position. It is their last gasp to cling to religion and delay the widespread outright rejection of god. That the dying candle of religion should finally burn out is inevitable because facts inevitably win in the end. Tobacco does cause cancer whether you admit it or not. Man-made climate change threatens our planet whether you choose to believe it or not. And there is no god to come and save us no matter how much you would like there to be. It’s all up to us and only us.

That makes me VERY encouraged. When merchants of doubt like William Irwin have to resort to manufacturing doubt, it is an admission that they know they cannot win on the merits of their position. It is their last gasp to cling to religion and delay the widespread outright rejection of god. That the dying candle of religion should finally burn out is inevitable because facts inevitably win in the end. Tobacco does cause cancer whether you admit it or not. Man-made climate change threatens our planet whether you choose to believe it or not. And there is no god to come and save us no matter how much you would like there to be. It’s all up to us and only us.

The public is obviously figuring that out. Too bad it is taking so long for the New York Times, once again, to stand for facts rather than propagating manufactured illusions of doubt on factual matters. I thank all the New York Times readers who posted their comments to this article and thereby reminding me that just because some professor of philosophy publishes some nonsense, even if it is published in the New York Times, many, many of us are simply not buying the doubt they’re selling any longer.

Let’s hope that desperate articles like this one are nothing more than the last gasps of a dying god.

Do you have one of those wacky friends? The ones with a deep, sincere, heartfelt conviction that Elvis still lives. That he is actually in seclusion preparing for his epic comeback? Busy rehearsing for the ultimate Elvis concert that will transform the world?

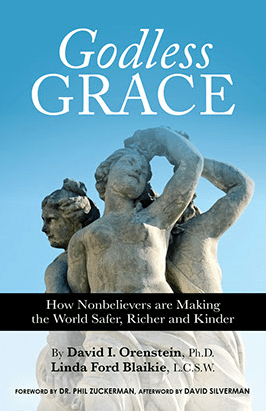

Do you have one of those wacky friends? The ones with a deep, sincere, heartfelt conviction that Elvis still lives. That he is actually in seclusion preparing for his epic comeback? Busy rehearsing for the ultimate Elvis concert that will transform the world? If you believe all grace comes from god, then the phrase “godless grace” probably sounds like an oxymoron to you. Or maybe even a blasphemy. You would probably maintain that grace cannot come from anywhere except from god.

If you believe all grace comes from god, then the phrase “godless grace” probably sounds like an oxymoron to you. Or maybe even a blasphemy. You would probably maintain that grace cannot come from anywhere except from god.